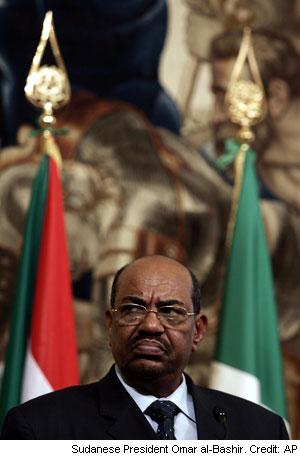

Last week’s move by the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, or ICC, to seek an arrest warrant for Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir introduces a new point of leverage with the Sudanese government and provides an opportunity for the U.N. Security Council to demand real changes in Khartoum’s policies and behavior. Unfortunately, the historical record suggests that the Council will likely miss this opportunity as it has missed many others during the past five years. This time, the Council must move quickly and use this leverage to help construct an effective peace process for Darfur, to provide meaningful protection for civilians, and to enact the right mix of carrots and sticks to convince various actors—Sudanese and external—to take the necessary steps to end the conflict.

If success at the Council was defined merely by volume of output, Sudan would be in great shape: Nine major resolutions have been adopted and 21 presidential statements have been issued since the start of the Darfur crisis in 2003 (see Annex)[1]. Yet the Darfur crisis has continued to deepen and the Council has unmistakably failed to live up to its responsibility to protect the people of Darfur and help restore peace and security in Sudan and the region.

As the Council’s member states consider their next steps, they ought to look carefully at the reasons behind their failure on Darfur, which has as much to do with how the Council works and its inherent structural limitations as it does with the substance of its resolutions. It has become painfully clear that Security Council members lack the political will to deal effectively with the Darfur crisis. Instead of strong support for the result of their own referral of the case of Darfur to the ICC, many Council members are considering how to suspend the case against Bashir without getting anything in exchange for this capitulation. Throughout the last five years, member states, including the United States, have positioned themselves to blame the U.N. while knowing full well they have not given the organization the resources, support, direction and will it needs to succeed.

This strategy paper will diagnose the underlying obstacles to effective Security Council response, providing a practical guide on how activists can better engage their governments to stop—and ultimately prevent—genocide and crimes against humanity.

1. THE BASICS

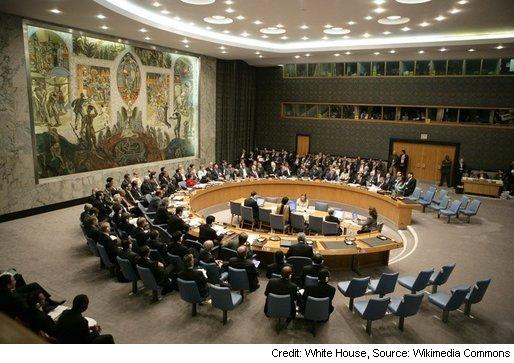

Article 24 of the Charter of the United Nations confers upon the Security Council “primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security,” a unique mandate in international law. Its 15 members have the power to impose sanctions, establish peacekeeping missions, and authorize military action in the name of international peace and security.

Not All Members Created Equal

The permanent membership of the Council—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—reflects the international balance of power at the time of the U.N.’s creation in 1945. These states have the power to veto Council resolutions, unlike the 10 rotating, non-permanent members of the Council who are elected by the General Assembly to serve two-year terms. What does this mean? Although the Council enjoys unrivaled legal weight in international relations, it remains a product of and a venue for politics and statecraft led by some of the world’s most powerful countries. The U.N. can be no more effective than its member states allow it to be.

Political Paralysis

During the Cold War, the veto threat exercised by the East and the West paralyzed the Security Council and relegated it to the sidelines of international politics. A window of cooperation opened as the Soviet block crumbled during the early 1990s, and a degree of consensus enabled the Council to support action against Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait and to authorize a humanitarian intervention in Somalia. But competing political interests stymied the Council’s ability to stop the genocide in Rwanda, end ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity in the Balkans in a timely fashion, or deal effectively with countless other threats to peace and security around the globe. Africa in particular has suffered from the Council’s frequent failure to take early, strong, and united action to prevent or halt deadly conflicts. The wars that tore apart the Great Lakes region, the interconnected conflicts in the Mano River countries in West Africa, and the now-deepening crises in Somalia and Zimbabwe have all occurred in full view of the Security Council, and member states have often preferred the rhetoric of condemnation that has not been backed by practical actions.

Not the Only Forum

The Security Council was not designed to be and has never served as the sole forum in which states congregate to transcend their differences and hammer together collective international security policy. Rather, the Council functions as an arena where states often struggle to win ground within the confines imposed by diplomatic understandings reached far from the U.N. building in Manhattan. These constraints are often defined—and often redefined—during concurrent meetings of regional bodies like the African Union, security alliances such as NATO, and above all through bilateral diplomacy between states. Most importantly, the core strategic decisions of member states are made in national capitals, not at the United Nations. In this sense, the Council is a diplomatic tool that states both use and abuse in their desire to act, give the appearance of acting, or block action on any particular international security issue.

The geopolitical landscape determines the extent to which states choose to employ or ignore the Council. In the case of Kosovo in 1999, NATO wound up striking against Serbia without Council authorization because of a Russian veto threat. Veto threats are not the only factor, however. Threats by key states to abstain on resolutions can result in deadlock or ineffective, watered-down language and toothless enforcement mechanisms.

The Political Mechanics of the Council

The Security Council functions through the interactions of its member state delegations. Decisions on resolutions or on non-binding presidential statements are negotiated in New York, but the key parameters are often set in national capitals. The international civil servants of the U.N. Secretariat and U.N. agencies (such as the U.N. Children’s Fund, or UNICEF, the World Food Program, and the World Health Organization) take a backseat during these deliberations, even as many states scapegoat them. The procedural aspects of the Council’s operation, such as the rotating presidency and the opportunities it affords a given state to drive the Council’s agenda, are one telling component of the Council’s elaborate rituals.

Member states also play a critical role in the implementation of Security Council resolutions. Subsidiary bodies established by resolutions, such as sanctions committees and working groups on issues such as counter-terrorism, are composed of representatives of Council members, and these members’ procedural and substantive decisions can make or break effective implementation. Absent sufficient political will, Security Council measures to stop crimes against humanity often simply die in committee.

Tragically, the case of Sudan, and in particular the response to Darfur, illustrates all too well the dysfunction of which the Council is capable.

2. INDECISION IN ACTION: THE CASE OF DARFUR

The first U.N. Security Council briefing exclusively devoted to Darfur was given by then Emergency Relief Coordinator Jan Egeland on April 2, 2004, already a year after the crisis had erupted. Four months later, the Council adopted Resolution 1556, which demanded that the government of Sudan disarm the janjaweed militias or face possible sanctions, and imposed a symbolic arms embargo on “non-governmental entities operating in Darfur.” The resolution lacked a robust enforcement mechanism and was disregarded on the ground as the situation deteriorated. The eight major subsequent resolutions have followed this depressing pattern of inefficacy.

Why so many resolutions to so little effect? Council failure was largely predetermined by an

As per instructions from their capitals, the United States, U.K., and a handful of other delegations at the U.N. were tasked with bullying their way into the little that could be achieved in New York absent broad high-level support. That approach gradually poisoned the atmosphere at the Council, created a thick layer of doubt regarding Anglo-American intentions, and played a part in inducing a number of critical abstentions, resulting in a litany of watered down and irrelevant statements.

Divided We Fall – the March 2005 Resolutions

From 2003 through the beginning of 2005, international diplomacy was crippled by the decision to concentrate on securing the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, or CPA, between Sudan’s ruling National Congress Party and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement at the expense of Darfur. Instead of seeking an all-Sudan solution, the United States allowed Darfur and the CPA processes to be played against each other. The strong rhetoric of the Security Council resolutions was belied by the unwillingness of the United States and its allies to risk confrontation with Khartoum because the CPA seemed within reach.

The signing of the CPA on January 9, 2005 created an opportunity for comprehensive Council action toward Sudan. Tragically, international consensus was not achieved, and what was intended to be one mega-resolution stalled in negotiations. It eventually metamorphosed into three separate resolutions, all adopted in March 2005. These resolutions exposed the fault lines within the international community on how best to deal with Sudan in its entirety.

Resolution 1590 established the U.N. Mission in Sudan, or UNMIS, to support CPA implementation. Resolutions 1591 and 1593 attempted to get tough on Khartoum over Darfur, extending the arms embargo, articulating a targeted sanctions policy, and referring the Darfur situation to the Prosecutor of the ICC. Though adopted unanimously, resolution 1590 demonstrated that there was no coherent international strategy to ensure the government of Sudan’s compliance. With striking inconsistency, the Council pledged collective allegiance as the “good cop” in Southern Sudan, while simultaneously feigning toughness with the very same interlocutors in Khartoum over Darfur—an approach which the government of Sudan easily saw through. Neither 1591 nor 1593 passed unanimously, indicating to Khartoum that the Council’s follow-through would be, at best, inconsistent.

Taken together, the March 2005 resolutions had the potential to outline an effective approach to Sudan through a dual focus on protecting the peace—and civilians—in the South, and providing the pressure to achieve a similar settlement in Darfur through sanctions and accountability measures. Ultimately, deep international divisions toward Sudan, manifested in the many abstentions to the two Darfur resolutions, undercut their viability. Absent consensus, the Security Council often lacks the political will to implement its own resolutions.

Compartmentalizing Sudan

The CPA contains the seeds for democratic reform across Sudan, and its effective implementation

The Security Council again demonstrated that it could only concentrate on one issue at a time, and even then it performed poorly. By focusing disproportionately on Darfur, the Council, along with others, lost focus on CPA implementation. The Council did not refocus on the CPA until the middle of 2007, by which point Darfur was in a deeper crisis and the CPA itself was facing possible collapse. Peace agreements had been produced for both Darfur and southern Sudan, but neither appears likely to bring lasting peace.

Preoccupation with Peacekeeping

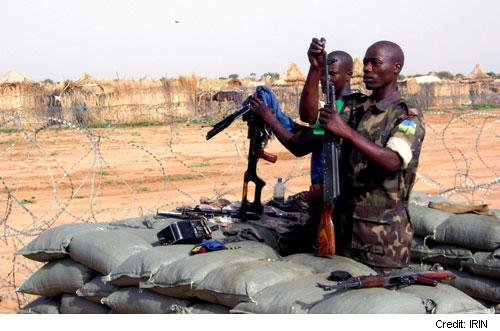

The signing of the ill-conceived and ill-fated DPA generated another misstep—the Council’s tunnel vision on getting a U.N. peacekeeping operation to take over from the underfunded, underequipped, and understaffed African Union force in Darfur, or AMIS. Observers who doubted the viability of the DPA were dismissed as naysayers, and the international community made limited efforts to lure or pressure the holdout rebel groups to sign[3]. As rebel groups reconfigured themselves for the next phase of the conflict, the Council experienced a bout of collective amnesia: the Council forgot lessons from comparable past conflicts and moved to deploy a peacekeeping force with no peace to keep and with no strength or mandate to impose its will. The A.U. has unfairly absorbed much of the blame for the lack of effective civilian protection in Darfur, but missteps by the Security Council and broken promises of its member states have continually compounded and exacerbated the situation.

The peacekeeping blunders began in May 2006 with Security Council Resolution 1679, in which the Council called for a U.N. peace operation with a disastrous caveat: Both Russia and China emphasized they had supported the resolution on the understanding that any U.N. deployment had to be acceptable to the government of Sudan. Discernibly hostile to an effective U.N. force in Darfur, Khartoum unsurprisingly refused to cooperate. The U.N. had accepted a pre-condition that made effective deployment virtually impossible.

Under domestic pressure to take action, the United States and U.K. forced the adoption of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1706 on August 31, 2006, mandating the U.N. Mission in southern Sudan, or UNMIS, to assume AMIS’ responsibilities in Darfur “no later than December 31, 2006.” The lack of adequate bilateral preparation and the impatience of the resolution’s sponsors came at a steep price—China, Russia, and Qatar abstained, again demonstrating the Council’s divisions and emboldening Khartoum. Within hours of the vote, the Sudanese government rejected the idea of a U.N. force in Darfur and Resolution 1706 was dead on arrival. The world community stood exposed—unwilling and unable to deploy an effective peacekeeping force to Darfur over Khartoum’s objections.

Chinese support eventually helped reach agreement in principle on a hybrid U.N./A.U. operation for Darfur in November 2006. But disagreement over the Council’s strategic approach was far from resolved and allowed Khartoum to continue its delaying tactics. It took the Council eight months, until July 31, 2007, to unanimously adopt Resolution 1769 and formally establish the U.N./A.U. Hybrid Operation in Darfur, or UNAMID. UNAMID was to take over AMIS by the end of that year, and it was to be the largest and most expensive peacekeeping operation ever run by the United Nations outside of the Balkans.

So far, UNAMID’s deployment progress has been inexcusably slow, impeded by a Sudanese government now accustomed to staring down the timid international community. In essence, the U.N. was asking the Sudanese government for permission to go in and stop the atrocities which the ICC chief Prosecutor has made clear are being directly orchestrated by the Sudanese government. It is small surprise that the mission is at a virtual standstill, and UNAMID now stands as a textbook case of how not to authorize, organize, and deploy peacekeepers. Full deployment is not expected until well into 2009 and it appears very likely—barring dramatic changes—that UNAMID will not be able to implement most of its mandate meaningfully for the rest of 2008, and perhaps for much longer[4]. Ominously and tragically, armed groups ambushed UNAMID peacekeepers on July 8 near El Fasher, killing 7 and injuring 22. Another peacekeeper was killed July 16. U.N. and A.U. officials have all but pointed the finger squarely at Khartoum and its janjaweed proxies.

Sanctions Undermined

U.N.-authorized sanctions against Sudan, established under Resolution 1591, have simply been an empty threat and affirmed Khartoum’s conviction that the Council lacks the political will to take strong action in the face of mass carnage. The resolution created a Sanctions Committee composed of Security Council members and supported by an independent Panel of Experts. But China and Russia used procedural machinations to ensure that the committee did not begin its work for more than a year and that even then it did not take meaningful action.

The Sanctions Committee has repeatedly delayed—or even prevented—the publication of reports of the independent Panel of Experts[5]. In January 2006, for example, the committee finally released the final version of the panel’s first report, having delayed its publication for the previous two months. The report detailed massive violations of the arms embargo, found multiple instances of breaches to the ban on offensive military flights, and, in a confidential annex, identified a list of 17 individuals impeding the peace process[6]. The Security Council did not act effectively on the findings[7].

Even worse, recent reporting by BBC has uncovered Chinese support for the Sudanese military in Darfur that, if accurate, would constitute a violation of the arms embargo[8]. This includes the supply of Chinese-manufactured military trucks that were shipped to Sudan in 2005, as well as the training of Sudanese fighter pilots who fly Chinese fighter planes in Darfur. Such behavior underscores the reality that until the Security Council member states decide to uphold their own resolutions, these measures are unlikely to impact insecurity on the ground in the region.

The Council and the Court

Resolution 1593 referred the Darfur situation to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal

3. PROSPECTS FOR IMPROVED PERFORMANCE

The case of Darfur illustrates the interconnection between Security Council activity and the wider context of international politics. With the U.S. government conserving scarce political capital for issues like Iraq and Iran, Sudan has remained considerably down the list of American priorities. In effect, the United States has used the mechanics of the Security Council to satiate domestic activist demand for a response on Darfur without spending the political capital necessary to get results. Most in the international community simply do not see the United States as being serious about resolving the situation. China, meanwhile, has used its veto-wielding position to block strong action against Khartoum, while Russia has largely followed suit. Both China and Russia should understand that over-use of their veto will simply push western democracies over time to work through other regional bodies and organizations that are more effective, such as in the example of NATO and European Union, cooperation in addressing the situation in Kosovo in the late 1999.

Several factors will affect the Security Council’s future effectiveness. First, China’s growing global influence, already evident in its expanding economic and diplomatic ties to Africa, will increasingly shape Council dynamics. Second, the degree to which the United States chooses to engage the Council meaningfully—and lead by example—will determine its relevance. The third factor is the outcome of continuing long-term efforts to reform the Council and make it more representative and transparent. Finally, the developing role of other international institutions—from security alliances such as NATO to regional bodies like the E.U. and the A.U.—will alter the context in which the Council functions.

CONCLUSION

The Security Council’s track record on Darfur could make a cynic out of the most optimistic of activists. But singularly blaming the Council as an institution is counterproductive. Instead, constituencies that care about Darfur and other places of conflict must focus on decisions made by individual member states and push their governments to invest the diplomatic capital to make Security Council resolutions more meaningful and follow-through more comprehensive. Concerted, consistent high-level engagement by the United States and its European allies will be critical to secure Chinese, Russian, and, importantly, African support or at least acquiescence. Only then will parties to the conflict in Darfur hear a single international voice that they will be unable to ignore or manipulate.

Efforts to deal with Darfur at the Security Council will not succeed until:

- Our leaders realize that resolutions “on the cheap” do not work and can even be counterproductive: Pushing issues to the Security Council without addressing significant policy differences between key member states results only in watered-down resolutions that embolden those directing Darfur’s tragedy, while giving the appearance of action.

- Political capital is committed: Absent increased attention to Sudan in bilateral contacts, aimed at resolving differences before the issue is tackled in New York, Council fragmentation will persist and Khartoum will continue to act with impunity.

- Resolutions are actually implemented, not merely adopted: Resolutions that create sanctions committees, peacekeeping missions, or peace processes are crucial, but become irrelevant without follow through. Council members must feel constant pressure to persevere with implementation, and to ensure that intransigent states and individuals are held accountable.

For all its faults, the Security Council remains indispensable to securing viable peace in Sudan and in other troubled spots around the world. When the Council speaks clearly, with one voice, no other institution can rival its authority and legitimacy. But renewed efforts to secure peace in Sudan will need to acknowledge that the rush to “do something” about Darfur at the Security Council, absent minimal strategic consensus among its permanent members and pivotal regional players, can be worse than doing nothing at all.

A consultant based in New York City helped in drafting this report.

| ANNEX: Major U.N. Security Council Resolutions on the Darfur Crisis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Stated Intent | Effect | Flaws | Abstentions |

|

1556 July 2004 |

|

Disregarded by all parties | Disregarded by all parties | No enforcement mechanism |

|

1564 September 2004 |

|

Disregarded by all parties | Abstentions undermined credibility of sanctions threat;no enforcement mechanism | China, Russia,Pakistan, Algeria |

|

1590 March 2005 |

|

Compartmentalized response to Darfur and South Sudan | Demonstrated incoherence of international strategy | None |

|

1591 March 2005 |

|

Disregarded by all parties; Sanctions against individuals blocked by Sanctions Committee |

No political will to implement | China, Russia,Algeria |

|

1593 March 2005 |

|

Investigation stonewalled by Khartoum | No pressure for Sudan to cooperate with ICC | China, US, Algeria,Brazil |

|

1672 April 2006 |

|

Negligible as sanctioned individuals had little foreign assets and did not travel | Signaled no will to sanction top leaders | China, Russia,Qatar |

|

1679 May 2006 |

|

Preoccupation with peacekeeping force doomed DPA | China and Russia insisted UN force be acceptable to Sudan | None |

|

1706 August 2006 |

|

Rejected by Sudan and within hours of adoption | Conditioned upon invitation from Khartoum | China, Russia,Qatar |

|

1769 July 2007 |

|

Full deployment not expected until 2009 | Allowed Sudanese veto over deployment | None |

Endnotes

[1] A total of 23 resolutions have been adopted on Sudan since the beginning of the Darfur crisis, but this report focuses on those with significant policy implications.

[2] See John Prendergast and Jerry Fowler, “Creating a Peace to Keep in Darfur: A Joint Report by the ENOUGH Project and the Save Darfur Coalition,” May 2008. Available at https://enoughproject.org/reports/creatingpeacedarfur

[3] This failure would come back to haunt the international community in more ways than one. The Justice and Equality Movement, or JEM, was dismissed in Abuja as politically reckless and militarily irrelevant. Less than two years later JEM launched an audacious assault on Sudan’s capital, reducing even further the chances for a negotiated settlement in the near future.

[4]See Joint ENOUGH/SDC Report on UNAMID, June 2008. The UN goal is to reach 80 percent deployment by the end of 2008 but, privately, UN staff admit this target would be extremely difficult to meet.

[5] Only “final” reports of the Panel have been formally published. All “interim” reports have never been officially released to the public.

[6] http://www.un.org/sc/committees/1591/reports.shtml

[7] The first—and so far the only—time the Council moved on its threat of targeted sanctions occurred on April 25, 2006, three months after the public release of the Panel’s report and days before the signing of the DPA. China, Russia and Qatar had blocked action at the Committee, which operates on consensual basis, and abstained on Resolution 1672, which named four persons for sanctions. None of the four had significant assets in foreign banks or indulged in foreign travel, so the impact of these sanctions was more symbolic than real. Resolution 1672 was largely an exercise aimed at deflecting criticism from constituencies in the United States and Europe which demanded greater accountability.

[8] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7503428.stm